|

Dark Night of the ‘Soul’ (What soul?)

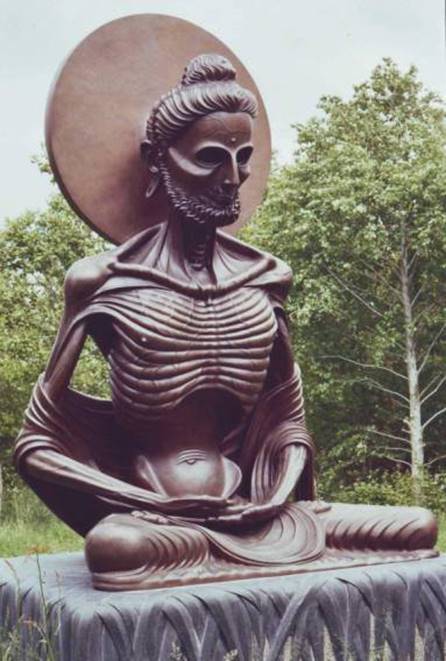

If the Split Man is ready to go but doesn’t have a goal, then the ascetic, i.e. the Fasting Buddha has decided on a goal, i.e. a problem to be solved, but doesn’t know how to get there. Sinking ever deeper into confusion, into darkness, into despair he concentrates ever harder but eventually utters a cry for help. Help comes in the form of a tiny glimmer of light (i.e. the solution) at the end of his dark tunnel. He grasps that light and, holding on because his life depends on it, increases that light (i.e. works out the implications of his solution as a new bit of knowledge) until it becomes the bright dawn of enlightenment. The Fasting Buddha sculpture represents the most intense or extreme concentration phase of problem solving. Some people experience this phase as a dreadful emptiness, one other, namely a Spanish monk with a well-developed capacity for (poetic) fantasy (mistaken for spirituality), as ‘the dark night of the soul.’ Everyone goes through this unhappy phase to reach the joyful white or golden light that shines forth at (goal) attainment, hence liberation from one’s problem. Many refuse to enter the dark tunnel because they fear the pain and hopelessness encountered there. But if they don’t enter the ‘dark night’ they cannot experience the attainment of the brilliant dawn of a new life and the sense of release and joy that brings. This unique

14ft 6ins bronze is a copy of a 2ft stone sculpture carved in the 1st

century AD in what is now Pakistan. It represents the yet unenlightened 1. ‘Whatever arises,

ceases.’ 2. ‘Things

arise subject to conditions; things cease subject to conditions.’ (all things

are relative) 3. ‘The 1st

condition for arising is contact (i.e. touch).’ (e.g. ‘Consciousness arises

from contact.’(that is to say, all things are momentary,

therefore quantised). *Note. After awakening (to wit: samma-sambodhi, whatever that means), Siddartha, the Sakyamuni, is said to have taken the name Tathagata (the meaning of the term is obscure). At no time during his 40 year career did the Sakyamuni ever refer to himself, nor did his followers refer to him, as ‘The Buddha’. The abstract appellation ‘the Buddha’ (to wit, ‘the man of bodhi’, originally meaning: knowledge) was the creation of a later age seeking popularity and political clout. So it was that the three refuges, namely taking refuge in the Buddha, the Sangha and the Dharma, were the creation of a later age. The Tathagata was far too smart to burden himself with followers and his followers with brothers, and to force them to take refuge in himself as pop idol, to wit, ‘The Great Wise One’, rather than seek to emulate the pressing function of generating perfect bodhi/knowledge. The very thought of a Sangha, i.e. a brotherhood, was anathema to the Sakyamuni who found his freedom in escaping social interaction, i.e. as when he dumped his wife and kid. It beggars belief that though Buddhist academics and learned priests of both vehicles are fully aware of the foregoing they yet choose to remain silent. No doubt they choose to lie (low) so as not to ruffle the feathers of their naïve financial supporters and so remain popular and travel 1st class. An inscription in the Ajanta caves (so Schopen) of about the 11th century AD refers to ‘followers of the Sakyamuni’ (of late correctly translated as ‘The Scythian Recluse’) rather than to Buddhists. |